Color Complex in Chess

It is widely believed that chess players see only two colors - black and white, or it can be said as dark and light. The space in a chess board comprises these colors, and time is the moves you make. Since it's a turn-based game, one has to make sure that every move count, and sometimes you just have to cleverly pass your move to your opponent to gain the upper hand via zugzwang. The man of encyclopaedic and impeccable knowledge, GM Sundararajan Kidambi explains the beautiful concept of color complex in chess with examples drawn from two games. Check out his enriching article. Photo: Shahid Ahmed

"முதல் எனப்படுவது நிலம் பொழுது இரண்டின்

இயல்பென மொழிப இயல்புணர்ந் தோரே"

(பொருளதிகாரம் அகத்திணையியல் தொல்காப்பியம்)

Roughly translated this deep statement of sage Tholkappiyar (dating to at least 4000 years ago) goes, "The inherent tendencies of Space and Time are the fundamentals - thus say the realized ones."

Applying this concept to Chess, Space consists of squares and Time consists of the move at hand. Time has varied other applications, so I will stick to looking at space in the present article.

The concept of Space (squares) in chess is one of the hardest to comprehend and one which would enhance the perception level of a player greatly. Understanding squares in one's own way is always enriching and this can be a continual journey in learning even by visiting games which are previously known too. For example I was recently browsing through the game Von Gottschall-Nimzowitsch, Hannover 1926 from the book Chess Praxis. The following position occurred after White's 18th move.

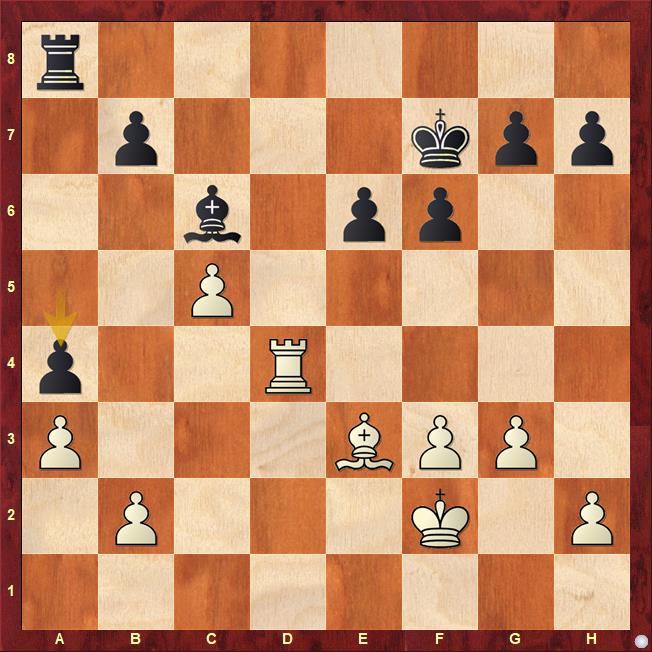

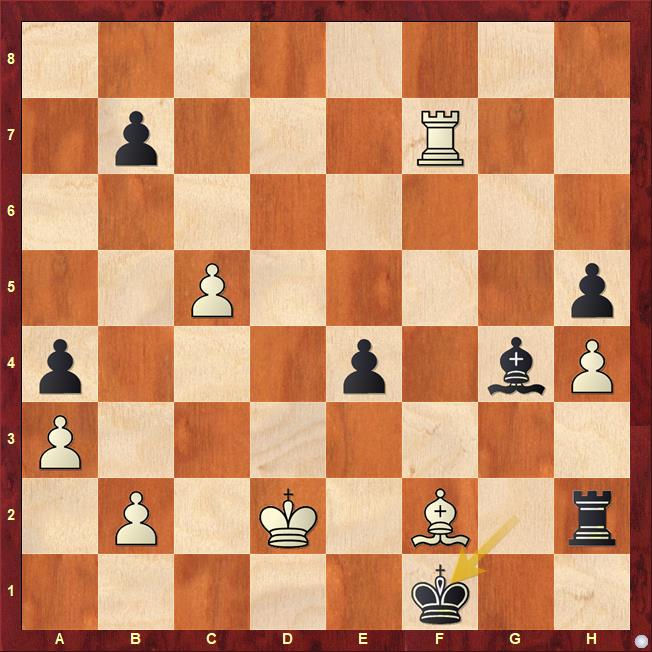

Von Gottschall - Nimzowitsch, Hanover 1926

Not an everyday position in an Isolated Queen Pawn structure, but the basic ideas still remain the same. Black has the Bishop pair in the endgame, but he is bit behind in development. White has more control of the key d5-square and threatens to play the d4-d5 pawn break. This gives a clue on how Black should continue to keep the game going. He continued with:

18... Bb4! 19.a3 Bxc3 20.Rxc3 Bd7

To a certain extent Black's decision of giving up his Bishop pair was surprising, but if we look at control of d5 square it is a logical one. To keep the Isolani in check is more important than holding on to the Bishop pair. Because White's central isolani is on a dark square and he only has a dark square Bishop left among his minor pieces, his control of light squares is not very good. His isolated pawn in itself is much less of a weakness than in other endgames in similar structures. It is easy to see that the d-pawn can be defended easily with the Bishop and Black's Rooks piling up on the pawn would be of no avail. Here White started drifting with

21.Rc5?! Rxc5 22.dxc5

The exchange operation looks absolutely natural at first glance. White gets rid of his isolated pawn, gets a queenside majority, connects his pawns and opens up the d-file!! Seriously, can anything be wrong with this?! Let us put aside the first appearances and take a deeper look at the position with fresh eyes. Like I mentioned earlier, the isolated d-pawn could not be considered as a weakness at all in this endgame as Black has no pieces to attack it. Even though White has a 3 vs 2 majority on the queenside if we pay attention to the placement of the pawns (especially the pawn on c5) we can see that pawns being placed on dark squares and the absence of the light square bishop means that Black's light square bishop and two pawns easily hold back White's 3 pawns on the queenside. There is no way for White to create a passed pawn at all! This means that Black's 4 vs 3 kingside majority is mobile and there is a potential to create a passed pawn. We also need to note that as long as White had the pawn on d4, Black had no majority on the kingside and the act of correcting White's pawns led to the creation of a potentially dangerous Black's kingside majority!

Going back to White's 21st move, he probably could have continued with 21.d5! Rxd5 22.Rxd5 exd5 23.Rc7 Bc6 24.Bxa7 which equalizes immediately or if 21...exd5 22.b4! Ra6 (21...Rb5 22.Bc5!) 23.Rxd5. Let us head back to the game continuation:

22...Bc6 23.f3 f6 24.Kf2 Kf7 25.Rd4

perhaps 25.b4!? came into consideration, to keep the queenside pawns connected. Nevertheless White will not be able to create a passed pawn as he would not be able to lift the light square blockade.

25....a5! 26.g3

It is hard to say if White should have played 26.b4 as this would have helped create an infiltration file for Black's Rook.

26..a4!

Black has made significant progress. His queenside pawns with support of the bishop hold back White's three pawns back effortlessly. He can now turn his attention to slowly but surely start mobilizing his kingside majority.

27.f4?!

White tries to hold back Black's majority (particularly e5 and g5) and outwardly it looks logical, but as we have already seen, the more White places his pawns on dark squares, the more he loses control of the light square complex. It is a good time to remember what Capablanca taught us about such positions as a general rule - to place the pawns on opposite color of the only remaining bishop. This would ensure that there would at least be a minimum control of both colors of the chessboard! Of course, one needs to see that the pawns themselves would not be a weakness in themselves if placed on light squares in this case. But as regards understanding the chess board with a view to square/color complex control, Capa's rule makes utmost sense! Going by this logic, it makes sense for White to go for

27.g4! instead with the idea of holding fort on the light squares with a subsequent h2-h3.

27...h5!

This is extremely logical, and Black clamps White's pawns down on dark squares and increases control of his light square complex. In positions with opposite colored bishops on the board with the presence of rooks, the side that tries to improve and go for a win needs to activate his king and use it as a strong attacking force. Black's move clears a path for his King to f5 via g6. King's activity, to the extent of almost being an extra piece in play in comparison with the opponent, depends on the concept of control of color complex. Pay attention to the fact that Black's king has an easy path to f5 and even further on the light squares, whereas White's King is heavily curtailed by his own pawns on the dark squares and by opponent's pieces on the light squares! In the end, this turns out to be the decisive factor in this game.

28.h3 Rh8!

This is not as difficult to understand as other mysterious rook moves of Nimzo. He simply stops g4,

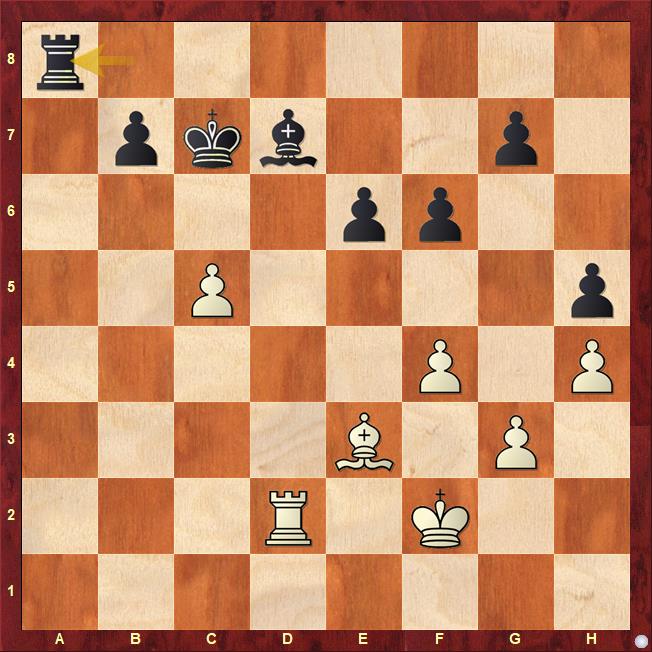

29.Rd1 Kg6 30.Rd4 Kf5 31.Bd2

Black has improved the position of his king, next in line is creating a passed pawn or mobilizing the kingside majority. Here he can create a passed pawn with e5 and after an eventual opening up of the f-file, use that to infiltrate White's camp, especially through the light squares e.g. f3! This explains his next mysterious rook move.

31...Rf8! 32.Be1 e5 33.fxe5 fxe5 34.Rh4 g5!

By using little tactical ideas, Black keeps expanding on the kingside.

35.Rb4 Ke6+ 36. Ke2 e4 37.Bf2 Rf3

Black has improved even further, he has created a passed e-pawn and also activated his rook on the third rank. White's pawn on h3 and b2 can be targets for attack.

38.Rb6 Ke5!!

An incredibly deep move. It is fairly obvious that Black needs to advance his king further to make progress, but it is not easy to see how to do it. So, Black uses all his ingenuity to make progress. In this particular position the idea is based on a famous endgame theme - namely the ZugZwang, but one that is quite easily missed in non-theoretical positions from my experience. Nimzowitsch's decision-making is based on prophylaxis, which constantly takes into account what one's opponent will do and either preventing it or making good use of it. This style was championed in a later day by Petrosian and Karpov! Here for example if Black had played 38....Kd5 39.Rb4 there is no easy progress. But to recognize that this position was a sort of mutual Zugzwang and the best decision is to pass the move on to the opponent always fascinates me!

39.Rb4 Kd5!!

So Black has managed to pass the move to his opponent. But what is the is significance behind it? Well, Black recognizes that White's Rook on b6 is not as secure as it would be on b4. To understand, let us take a look at this line - 40.Rb6 would have been answered by 41...h4! 42.gxh4 gxh4 43.Bxh4 Kxc5! gaining an important tempo, attacking the rook on b6 44.Rb4 Rxh3 -+. We have seen the importance of space (squares) earlier, this instance also shows the importance of the other important element on the chessboard - Time.

40.h4 gxh4 41.gxh4 Rh3

The opening up of the third rank has increased the sphere of influence of the Rook. Now, Black keeps an eye on the h4 pawn. This severely restricts the bishop on f2 which is burdened ever more to defend both the c5 and h4 pawns.

42.Rd4+ Ke5 43.Rd8 Bd5!

Black takes the time to shut the d-file and threatens to play Rb3 in order to win the b2-pawn. While White is hard-pressed to defend against this, Black would use the time to advance further along the open lines created in the kingside with his king.

44.Re8 Be6 45.Rd8 Kf4

Here it was perhaps better for Black to first shake White's king away from e2 so that he can get an entry point on f3 for his own king. For example he could have started with 45...Bc4+! 46.Kd2 Bd5! (once again threatening Rb3) 47.Re8 + Kf5 48.Rf8 Kg4 when it is too difficult to hold back the relentless march of Black's monarch. White just has too many weaknesses (b2, c5, h4) to contend with and once black king reaches f3, he would sooner or later shepherd the e-passed pawn to a queen.

46.Rf8+ Bf5

Here too 46...Kg4 was an idea

47.Rf7 Rh2 48.Re7?!

Here it was better to play 48.Kf1 as analyzed deeply by Huebner, but I refrain from giving the same as the lines are very deep and complicated and shifts the focus from the primal idea of the article. I will attach the analysis as a link to a replayable board at the end of the article.

48...Bg4+ 49. Ke1 Kf3 50.Rf7+ Kg2

Note how Black's King walks up right into White's rear through the weakened light squares.

51.Kd2 Kf1!

Triumph of Black's strategy! Black won soon after

52.Ke3 Bf3 53.Bg3 Rxb2 54. Bd6 Rb3+ 55.Kd4 Kf2 56.Rg7 e3 57.Bg3 Kf1 58.Rf7 e2 59.Re7 Bc6 0-1

A truly thought provoking game which had many moments worth observing minutely. Looking at this game, I was reminded of another not too popular game which I had seen in the amazing book Bobby Fischer - A study of his approach to chess by Elie Agur. I decided to take another look at that one too and it appeared to show me, a new side of itself! Let us join the action after White's 10th move

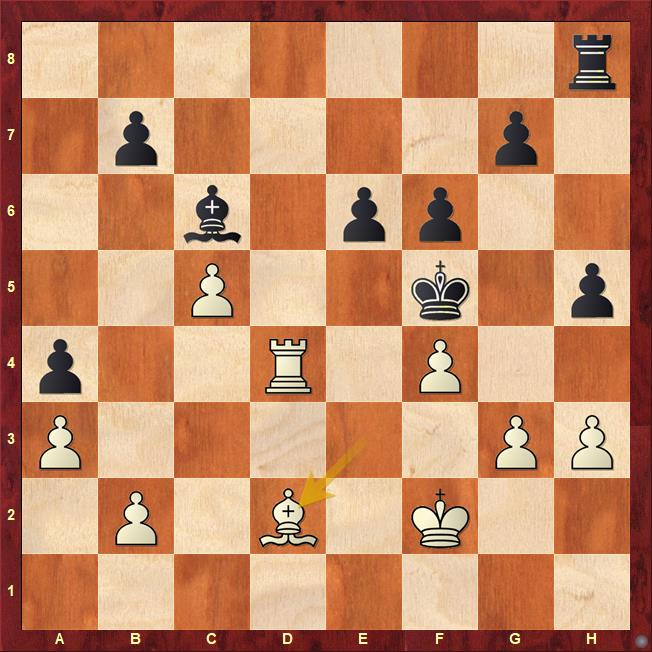

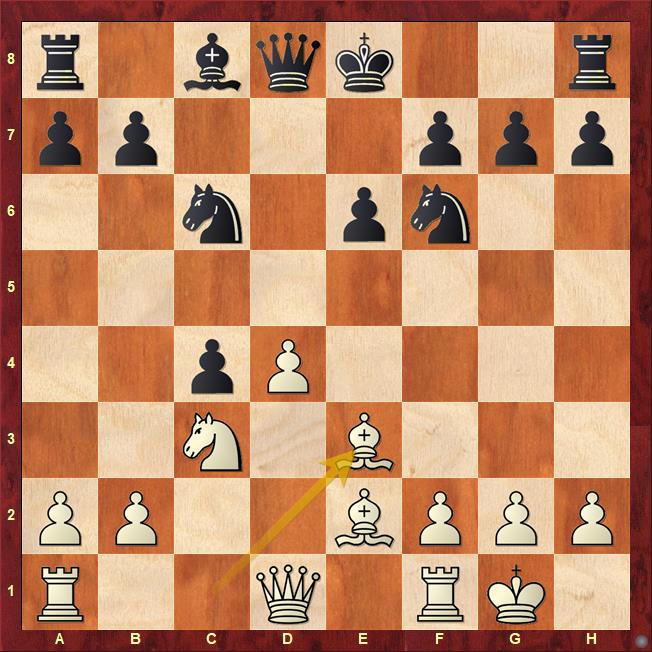

Pachmann - Fischer, Havana Olympiad 1966

Position after 10.Be3

We are out of an obscure opening position in an IQP again, and this time Fischer continued with

10...Na5!

He defended the extra pawn and forces White to accept a favorable trade of minor pieces i.e. to give up his light square bishop for Black's knight.

11.Bxc4 Nxc4 12.Qa4+ Bd7 13.Qxc4 Bc6

Black got his light square Bishop to the ideal square of c6 from where it bolsters the d5 square for an eventual Blockade and also controls the long diagonal and makes the absence of White's light square Bishop felt more keenly.

14.Bg5!

Of course White is not going to sit and lay down his arms, he rightly fights for the control of d5-square.

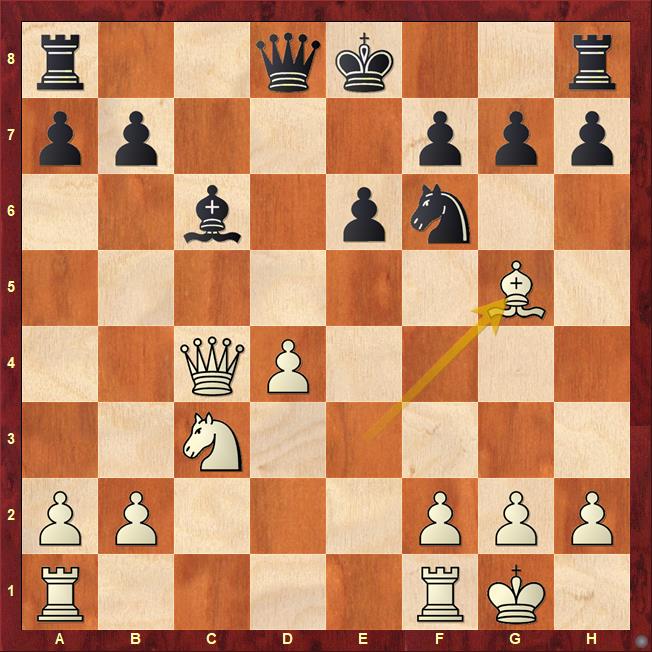

Position after 14.Bg5

Here Fischer typically continued with a combative

14...Qa5!? instead of a simpler move like 14...0-0. He was willing to accelerate the tension in a position and test its dynamic potential. White replied

15.Qc5?

Carrying forward the lessons from the last game, this is clearly a step in the wrong direction. He loses the dynamism inherent in the position totally and also Black is clearly much better prepared for the endgame with his king in the center. A surprising error from a player such as Pachman! He should have continued 15.Bxf6 gxf6 and sacrificed a pawn at a suitable moment with d4-d5. trying to play against Black's King in the center. The game perhaps would have been in dynamic balance.

15...Qxc5 16.dxc5 a5!

Just as in the Nimzowitsch's game, this pawn advance stops white from connecting his queenside pawns and his majority is stymied before it even started!

17.Rfd1

Outwardly it seems that White can hardly have any dangers in the position, but this is highly deceptive. Here Fischer came up with the brilliant

17...h5!!

I love this concept. Since Black needs the king in the center, in the endgame, he does not want to castle. This means that he needs to activate his king's rook, so he starts with h5 and if given time he would activate his rook after an eventual h5-h4 and Rh5. The rook pawn advance also has an idea of increasing the power of the long diagonal bishop with an eventual h4-h3 if allowed. Of course with this thought process in mind, one needs to expect opponent's most likely response. In this case it is

18.h4

So, Black's earlier ideas listed came to a standstill. Does that mean he didn't have any deeper idea? This is far from the truth, Fischer understood that White would play h4 and this would in turn place White's pawns on the dark squares which leads to losing control of light squares. We have seen this in Nimzo's game too, if White places more pawns on the same color of his Bishop the opposite color complex becomes weak and invites opponent's pieces to occupy them. Fischer is a master of timing, he induces White to fix the pawn on a dark square with h4 which will weaken White's light squares in the long run.

18...Nd7!

Having isolated the c-pawn, Black next threatens it. Not 18..Nd5 19.Ne4!

19.Be3 Ne5 20.Bd4 Nd7 21.b3

Of course 21.Bd4 Rg8 and then Black takes on g2 does not make any sense for White.

21....Rg8!

with the idea g7-g5.

22.Be3 Ne5

the Knight comes back after the g7 pawn is protected.

23.f3 Ng6 24.Bf2 Nf4

Black's knight maneuvering is pretty impressive. With every little move he is making White commit some weakness.

25.Be3 Nd5!

After traversing a lot of squares the knight comes back to d5, but after forcing some changes in White's position. Note that in this position White's Bishop on e3 is unprotected which forces a knight exchange.

Compare this position with the one after White's 18th move for better understanding of the little differences.

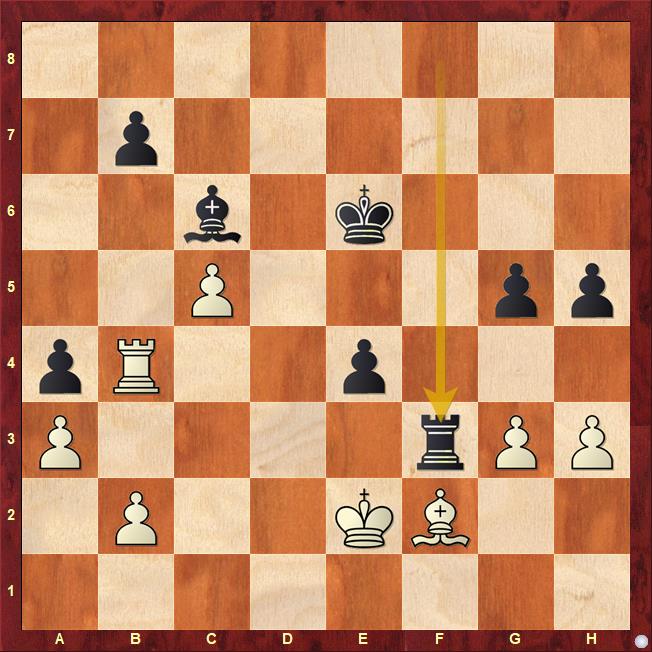

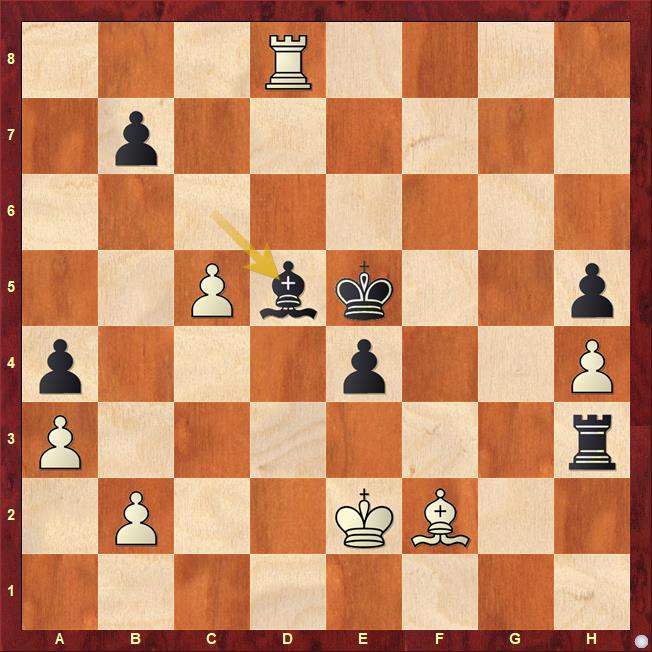

26.Nd5 Bd5 27.Rd4 Kd7 28.Rc1 Kc6

Black's king feels at home on c6. Note how each and every unit of Black's is patiently improved and it all falls into a perfect picture!

29.Rc3 f6! 30.f4

Once again White's idea to hold back Black's majority (especially e6-e5 and g7-g5) seems very natural. But once again as we have seen in Nimzo's game the more White places his pawns on dark squares, the more he loosens his light square complex. It is enjoyable to observe how Black makes White dance together to his tunes!

30...Rgd8 31.Kf2 a4!

Once again wonderful timing. Black takes the opportunity to either open up the a-file for activating his rook or force White to further weaken his pawn structure on the queenside. Reminiscent of Nimzo's game again!

32.Rxa4 Rxa4 33.bxa4 Bxa2 34.Rc2 Bd5 35. Rb2 Ra8 36.Rb4 Ra5

Fixing the weakness on a4, White's pieces are absolutely helpless. To begin with he is going to lose his pawn on a4.

37.g3 Kc7 38.Bd4 Bc6 39.Be3 Bxa4 40.Rd4 Bd7 41.Rd2 Ra8 42.Rb2 Rb8 43.Rd2 Ra8

In this adjourned position, Pachman resigned! Although it may seem a bit premature, he saw no defence against the slow but sure king march of black to f5 or g4 via d8-e8-f7-g6. His bishop would occupy a great square on d5 and Black has all the freedom to attack White's weakness, whereas White is completely helpless to even create a semblance of a threat to Black. A wonderful game where Fischer used all of Nimzowitch's ideas in an improved fashion.

Conclusion

1.Space is an important factor, and in chess we can understand it in terms of squares.

2.To extend it further we can understand it in terms of color complexes

3.How one side dominates the other by using this dimension of space may be the key to enhancing one's perception about the great game.

Fischer imbibed chess as a child learns a language, intuitively and individually. Let us celebrate the individuality and innate intelligence inherent in each one of us. Adios

Replay the games

(In Nimzowitsch's games Huebner's analysis has been included too from Mega and clearly indicated.)

About the author

ChessBase India is happy to see GM Sundararajan Kidambi writing his fourth post of the year in his blog "Musings on Chess". Knowing what an encyclopedic knowledge the grandmaster from Chennai possesses, I think we are in for a treat! One can only hope that Kidambi continues writing regularly! We will keep reminding him about it!

Links

The article was edited by Shahid Ahmed